28 May - 3 June 1917

- By Mark Sutcliffe

- •

- 03 Jun, 2017

- •

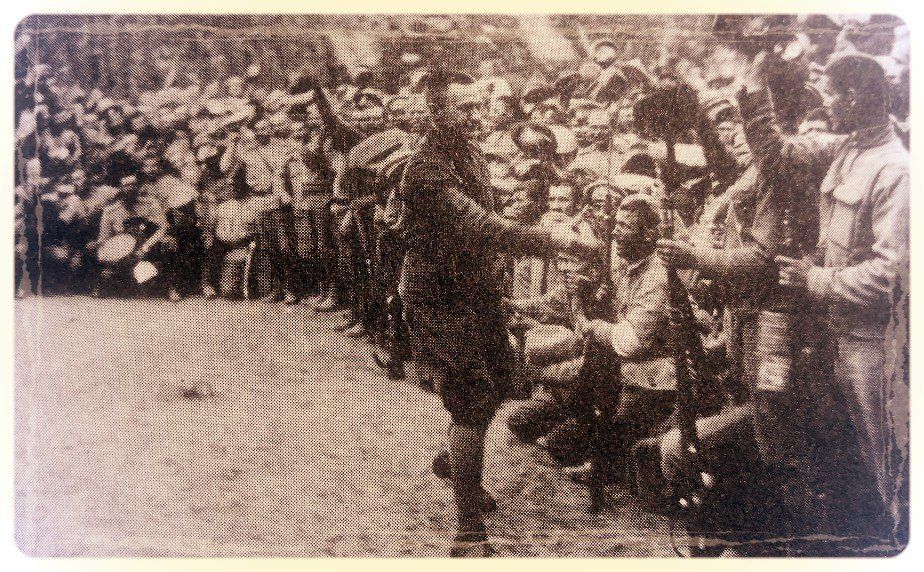

An offensive was scheduled for mid-June. Kerensky’s personal

contribution to it consisted in rousing the troops with patriotic speeches;

these had an enormous immediate effect which evaporated as soon as he departed.

The generals, trying to command an increasingly undisciplined army, regarded

such rhetoric sceptically, dubbing the Minister ‘Persuader in Chief’. The will

to fight was no longer there. According to Kerensky, the Revolution had

persuaded the troops that there was no point in fighting. ‘After three years of

bitter suffering’, he recalled, ‘millions of war-weary soldiers were asking

themselves: “Why should I die now when at home a new, freer life is only

beginning?”’ The malaise was encouraged by the ambivalent attitude of the

Soviet, which continued to urge them to fight in the same breath that it

condemned the war as ‘imperialist’.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, London 1995)

28 May

Article in the Sunday Times

This revolution is the most colossal social upheaval the world

has ever known. It has not fallen on a soil well prepared in advance, but has

fallen as a bombshell amongst 150 million of people, 80 per cent of whom are

ignorant peasants. It is hardly understood in this country that the revolution

is now the one paramount interest to the peasant’s mind, that the war occupies

but a very secondary place in his thoughts.

E. Ashmead Bartlett, ‘Our Task Ahead’, Sunday

Times

29 May

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

Public opinion is as changeable as a summer day – and today

my British colleagues feel pessimistic as regards the socialists, who they say

are ‘agin’ everybody and prepared to make friends with no one.

(Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright, London 2002)

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

We went for a drive in a car through the immense

park [at Peterhof], where the roots of the great trees are bathed by the blue

waters of the Gulf of Finland. The park is filled with statues, colonnades,

pavilions, hermitages, kiosks, boskets, fountains, pools and water follies,

each one prettier than the last … Unfortunately, this splendid scene is defiled

by the crowds of soldiers who wander about, all unbuttoned and filthy,

sprawling on the lawns and grass walks and reading out their proclamations

under the colonnades … they were dressing on the terrace, whose marble

balustrades were hung with their thrown off clothes and their doubtful

underwear … the reign of the people is hardly an aesthetic one and when I saw

them I thought of how, in the past, in many of the towns of Russia there were

placards outside the park gates, forbidding the entry of ‘soldiers and dogs’.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918, London 1969)

1 June

By the first week of June it became clear that Kronstadt,

Tsaritzin and Krasnoyarsk were only Bolshevik islands. The rest of the country

was following the lead of the parties of compromise.

(M.P. Price, My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution, London 1921)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval cadet at Kronstadt

By June 1917 Kronstadt had been firmly mastered by our

Party. True, we did not have a majority even in the Soviet there, but the

actual influence of the Bolsheviks was, in essentials, unlimited … long before

the October Revolution, all power in Kronstadt was de facto in the hands of the

local Soviet – in other words, was held by our Party, which actually guided the

Soviet’s current activity.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first published 1925)

Emmeline Pankhurst arrived in Petrograd in early June 1917

‘with a prayer from the English nation to the Russian nation, that you may

continue the war on which depends the face of civilization and freedom’. She

truly believed, she insisted … ‘in the kindness of heart and the soul of

Russia’.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution, London 2017)

Letter from Sofia Yudina in Petrograd to her friend Nina Agafonnikova from Vyatka

We’ve just eaten, Lena has started practising [on the piano]

and I’ve gone to the studio. As soon as Lena finishes playing I will play. I

play three or four hours every day … In the evening it’s boring: the Toropovs aren’t here yet … we

haven’t been getting papers or letters for ages, and have no idea how to send

the letters we write … Papa’s and Mama’s moods are not good, and it’s very sad

and worse than anything, perhaps. The mood of the local peasants is fine and

sympathetic, for the moment this all seems peaceful. They seem to react to

events in a very sensible, sane way, as far as we can tell from talking to

them. They’re interested in how the revolution came about in Piter, what’s

happened to the tsar, where he is, what they’re now doing with him…

(Viktor Berdinskikh, Letters from Petrograd: 1916-1919, St Petersburg 2016)

2 June

Report on a speech by the Russian Chargé

d'Affaires

In addressing you I am appealing to a certain portion of the

British people, who, after the war, will help Russia to rebuild the industrial

fabric of my country. I venture to say that of all the peoples allied for the

purpose of exterminating once and for all the poisonous gas of Prussianism, I

do not think that any two have manifested in a clearer and more striking manner

their deep-rooted desire for national and permanent friendship than Great

Britain and Russia. (Cheers.) They are allies not only in arms but in peace.

M. Nabokoff, Minister Plenipotentiary in charge of the

Russian Embassy in London, ‘Russia’s Duty to her Allies’, The Times

3 June

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Yalta. Princess Serge Dolgoruki died quite suddenly at the

age of thirty-six, leaving six children by a former husband – the eldest only

thirteen – and one little Dolgoruka. She has been unconscious for two days from

a mistaken dose of veronal. She is to be buried on Wednesday. She was a

charming lady, loved by everybody, and was an intimate friend of the Grand

Duchess Xenia. Her death has greatly upset us all.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917, New York 1919)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3 June 2017

De Robien’s comments (29 May) about the ‘filthy’ and ‘unbuttoned’ soldiers at Peterhof are indicative of how much the Russian army had changed since the Revolution but they were only exercising their new privileges. An article by Robert Feldman (Soviet Studies, 1968) describes how quickly military authority broke down after the change of regime. The tsarist military code (articles 99, 100, 101, 102 and 104 to be precise) forbade the Russian soldier from smoking in the street, riding inside tramcars, frequenting clubs and public dances, and eating in restaurants or other places where drinks were sold. He wasn’t allowed to attend public lectures or theatrical performances, or even read books or newspapers without first having them vetted by his commanding officer. The Petrograd Soviet did away with these ‘degrading regulations’, giving soldiers complete civic freedom. This in turn alarmed the army’s high honchos, like Generals Ruzsky on the Northern Front and Alekseev, Chief of Staff, who pleaded with the new Minister of War Guchkov to prevent the ‘disease of disintegration’. Kerensky’s morale-raising tour of the front had only short-lived impact and by 1 June – just three weeks before a planned offensive against the Germans – he had replaced Alekseev along with the commanders of four of the five fronts. Feldman sums up the subsequent June offensive as dealing the Russian army ‘a blow from which it was never to recover’.

8 October

Letter from Lenin to the Bolshevik Comrades attending the Regional Congress of

the Soviets of the Northern Region

Comrades, Our revolution is passing through a highly critical period …

A gigantic task is being imposed upon the responsible leaders of our Party,

failure to perform which will involve the danger of a total collapse of the

internationalist proletarian movement. The situation is such that verily,

procrastination is like unto death … In the vicinity of Petrograd and in

Petrograd itself — that is where the insurrection can, and must, be decided on

and effected … The fleet, Kronstadt, Viborg, Reval, can and must advance

on Petrograd; they must smash the Kornilov regiments, rouse both the capitals,

start a mass agitation for a government which will immediately give the land to

the peasants and immediately make proposals for peace, and must overthrow

Kerensky’s government and establish such a government. Verily, procrastination

is like unto death.

(V.I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin, The Russian Revolution: Writings and Speeches

from the February Revolution to the October Revolution, 1917, London 1938)

9 October

Report in The Times

The Maximalist [Bolshevik], M. Trotsky, President of the Petrograd Soviet,

made a violent attack on the Government, describing it as irresponsible and

assailing its bourgeois elements, ‘who,’ he continued, ‘by their attitude are

causing insurrection among the peasants, increasing disorganisation and trying

to render the Constituent Assembly abortive.’ ‘The Maximalists,’ he declared,

‘cannot work with the Government or with the Preliminary Parliament, which I am

leaving in order to say to the workmen, soldiers, and peasants that Petrograd,

the Revolution, and the people are in danger.’ The Maximalists then left the

Chamber, shouting, ‘Long live a democratic and honourable peace! Long live the

Constituent Assembly!’

(‘Opening of Preliminary Parliament’, The Times)

10 October

As Sukhanov left his home for the Soviet on the morning of the 10th, his

wife Galina Flakserman eyed nasty skies and made him promise not to try to

return that night, but to stay at his office … Unlike her diarist husband,

who was previously an independent and had recently joined the Menshevik left,

Galina Flakserman was a long-time Bolshevik activist, on the staff of Izvestia.

Unbeknownst to him, she had quietly informed her comrades that comings and

goings at her roomy, many-entranced apartment would be unlikely to draw

attention. Thus, with her husband out of the way, the Bolshevik CC came

visiting. At least twelve of the twenty-one-committee were there … There

entered a clean-shaven, bespectacled, grey-haired man, ‘every bit like a

Lutheran minister’, Alexandra Kollontai remembered. The CC stared at the

newcomer. Absent-mindedly, he doffed his wig like a hat, to reveal a familiar

bald pate. Lenin had arrived.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai

Sukhanov

Oh, the novel jokes of the merry muse of History! This supreme and decisive

session took place in my own home … without my knowledge … For such a

cardinal session not only did people come from Moscow, but the Lord of Hosts

himself, with his henchman, crept out of the underground. Lenin appeared in a

wig, but without his beard. Zinoviev appeared with a beard, but without his

shock of hair. The meeting went on for about ten hours, until about 3 o’clock

in the morning … However, I don’t actually know much about the exact

course of this meeting, or even about its outcome. It’s clear that the question

of an uprising was put … It was decided to begin the uprising as quickly

as possible, depending on circumstances but not on the Congress.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

11 October

British Consul Arthur Woodhouse in a letter home

Things are coming to a pretty pass here. I confess I should like to be out

of it, but this is not the time to show the white feather. I could not ask for

leave now, no matter how imminent the danger. There are over 1,000 Britishers

here still, and I and my staff may be of use and assistance to them in an

emergency.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2017)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval

cadet at Kronstadt

The proximity of a proletarian rising in Russia, as prologue to the world

socialist revolution, became the subject of all our discussions in

prison … Even behind bars, in a stuffy, stagnant cell, we felt instinctively

that the superficial calm that outwardly seemed to prevail presaged an

approaching storm … At last, on October 11, my turn [for release]

came … Stepping out of the prison on to the Vyborg-Side embankment and

breathing in deeply the cool evening breeze that blew from the river, I felt

that joyous sense of freedom which is known only to those who have learnt to

value it while behind bards. I took a tram at the Finland Station and quickly

reached Smolny … In the mood of the delegates to the Congress of Soviets

of the Northern Region which was taking place at that time .. an unusual

elation, an extreme animation was noticeable … They told me straightaway

that the CC had decided on armed insurrection. But there was a group of

comrades, headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who did not agree with this decision

and regarded a rising a premature and doomed to defeat.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first

published 1925)

12 October

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

On [Kerensky] expressing the fear that there was a strong anti-Russian

feeling both in England and France, I said that though the British public was

ready to make allowances for her difficulties, it was but natural that they

should, after the fall of Riga, have abandoned all hope of her continuing to

take an active part in the war … Bolshevism was at the root of all the

evils from which Russia was suffering, and if he would but eradicate it he

would go down to history, not only as the leading figure of the revolution, but

as the saviour of his country. Kerensky admitted the truth of what I had said,

but contended that he could not do this unless the Bolsheviks themselves

provoked the intervention of the Government by an armed uprising.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

13 October

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky is becoming more and more unpopular, in spite of certain grotesque

demonstrations such as this one: the inhabitants of a district in Central

Russia have asked him to take over the supreme religious power, and want to

make him into a kind of Pope as well as a dictator, whereas even the Tsar was

really neither one nor the other. Nobody takes him seriously, except in the

Embassy. A rather amusing sonnet about him has appeared, dedicated to the beds

in the Winter Palace, and complaining that they are reserved for hysteria

cases … for Alexander Feodorovich (Kerensky’s first names) and then

Alexandra Feodorovna (the Empress).

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917–1918, London 1969)

14 October 2017

The BBC2 semi-dramatisation of how the Bolsheviks took power, shown this week,

was a curious thing. Talking heads in the form of Figes, Mieville, Rappaport,

Sebag-Montefiore, Tariq Ali, Martin Amis and others were interspersed with

moody reconstructions of late-night meetings, and dramatic moments such as

Lenin’s unbearded return to the Bolshevik CC (cf Sukhanov above). The programme

felt rather staged and unconvincing, with a lot of agonised expressions and

fist-clenching by Lenin, but the reviewers liked it. Odd, though, that

Eisenstein’s storming of the Winter Palace is rolled out every time, with a

brief disclaimer that it’s a work of fiction and yet somehow presented as

historical footage. There’s a sense of directorial sleight of hand, as if the

rather prosaic taking of the palace desperately needs a re-write. In some

supra-historical way, Eisenstein’s version has become the accepted version.

John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World

, currently being

serialised on Radio 4, is also presented with tremendous vigour, and properly

so as the book is nothing if not dramatic. Historical truth, though, is often

as elusive in a book that was originally published — in 1919 — with an

introduction by Lenin. ‘Reed was not’, writes one reviewer, ‘an ideal observer.

He knew little Russian, his grasp of events was sometimes shaky, and his facts

were often suspect.’ Still, that puts him in good company, and Reed is

undoubtedly a good read.