13-19 August 1917

- By Mark Sutcliffe

- •

- 19 Aug, 2017

- •

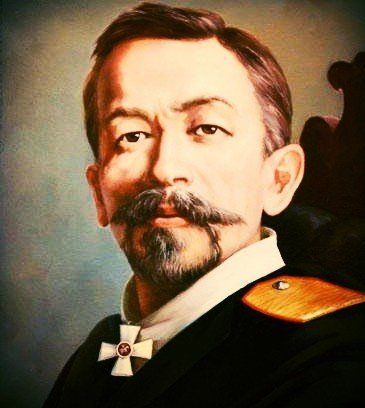

British journalist Morgan Philips Price, reporting on Kornilov in August 1917

13

August

Message from President Wilson to the National Conference in Moscow

I take the liberty to send to the members of the great council now meeting

in Moscow the cordial greetings of their friends, the people of the United

States, to express their confidence in the ultimate triumph of ideals of

democracy and self-government against all enemies within and without, and to

give their renewed assurance of every material and moral assistance they can

extend to the Government of Russia in the promotion of the common cause in

which the two nations are unselfishly united.

(Russian-American Relations: March 1917-March 1920, New York 1920)

14

August

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy,

Petrograd

No news of Moscow conference today, no papers being published, and telephone

connection with Moscow very poor. We have extended one hundred million dollars

more to Russia with the distinct proviso, however … that it is to be expended

for specific purposes ‘on the condition that Russia continues the struggle

against the common enemy.’

(Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J.

Butler Wright, London 2002)

When [Kornilov] arrived in Moscow on August 14, over Kerensky’s objections,

to attend a State Conference, he was wildly cheered. For Kerensky, who regarded

Kornilov’s reception as a personal affront, this incident marked a watershed.

According to his subsequent testimony, ‘after the Moscow conference, it was

clear to me that the next attempt at a blow would come from the right and not

from the left’.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution ,

London 1995)

Diary of Zinaida Gippius

Kerensky is a railway car that has come off the tracks. He wobbles and sways

painfully and without the slightest conviction. He is a man near the end and it

looks like his end will be without honour.’

(Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy, London 1996)

Valia Dolgorukov to his brother Pavel from Tobolsk

My dear Pavel,

We arrived in Tobolsk at 6 in the evening. In order to see the house and

find out what had been prepared, Makarov and I decided to go into town before

the others and do a reconnaissance. The picture was depressing in general, and

in complete contrast to Ivan’s description … a dirty, boarded up, smelly house

consisting of 13 rooms, with some furniture, and terrible bathrooms and toilets

… This is the seventh day when we are cleaning, painting and getting the houses

in order while we and the family are still on the steamboat Russia. The cabins

are very small and the facilities, for women at least, miserable. Alexei and

Maria have caught cold. His arm is hurting a lot and he often cries at night. Gilliard

has been lying in his cabin for the last eight days, he has some sort of boils

on his arm and legs. And a slight fever. It is easier to get provisions here

and significantly cheaper. Milk, eggs, butter and fish are plentiful. The

family is bearing everything with great sang-froid and courage.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion, London 1996)

18 August

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to the Imperial Court

I could not … conceal from [Kerensky] how painful it was to me to watch what

was going on in Petrograd. While British soldiers were shedding their blood for

Russia, Russian soldiers were loafing in the streets, fishing in the river and

riding on the trams, and German agents were everywhere. He could not deny this,

but said that measures would be taken promptly to remedy these abuses.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

19 August

All rumours of incipient coups notwithstanding, after the Moscow conference,

Kerensky was willing to accept the crushing curbs on political rights that

Kornilov demanded, hoping they might stem the tide of anarchy … Kornilov

pressed his advantage. On 19 August, he telegraphed Kerensky to ‘insistently

assert the necessity’ of giving him command of the Petrograd Military District,

the city and areas surrounding. At this, though, Kerensky still drew the line.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London

2017)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

19 August 2017

I keep claiming to be through with historical parallels, but sometimes they're hard to avoid. August is a strange month when politics takes time off and journalists hunt around for things to write about. In Russia August seems to be a month for abortive coups: Kornilov's in 1917; the putschists in 1991. In both instances the coup's failure in the short term heralded the government's demise a little further down the line, and helped bring to power regimes antipathetic to the coup's aims. In 1917 it was the Bolsheviks; in 1991, it was Boris Yeltsin, President of the Russian Federation, whose resistance to the coup enhanced his popular support. For those who may have forgotten the chain of events in 1991, here's a potted resume:

'The coup of August 1991 was timed to prevent the signing of the new Union Treaty which would have fundamentally recast the relationship between the centre and the republics in favour of the latter, and was scheduled for 20 August. On 18 August, a group of five military and state officials arrived at Gorbachev’s presidential holiday home on the Crimean coast to attempt to persuade him to endorse a declaration of a state of emergency. Gorbachev’s angry refusal to do so was the first indication that the coup plotters had miscalculated. While Gorbachev was held virtual prisoner, the State Committee ordered tanks and other military vehicles into the streets of the capital and announced on television that they had to take action because Gorbachev was ill and incapacitated. Some of the republics’ leaders went along with the coup; others adopted a wait-and-see approach. A few declared the coup unconstitutional. Among them was Yeltsin who made his way to the White House, the Russian parliament building, and, with CNN’s cameras rolling, mounted a disabled tank to rally supporters of democracy. The soldiers and elite KGB units ordered into the streets by the State Committee refused to fire on or disperse the demonstrators. By 21 August the leaders of the coup had given up. An exhausted Gorbachev returned to Moscow to find it totally transformed. When he visited the Russian parliament, Yeltsin's stronghold, he was humiliated by Yeltsin and taunted by the deputies. Reluctantly, he agreed to Yeltsin's dissolution of the Communist Party which was held responsible for the coup and resigned as the party’s General Secretary. Yeltsin thereupon proceeded to abolish or take over the institutions of the now moribund Soviet Union' (Lewis Siegelbaum). I remember August 1991 well since I was supposed to be flying to Moscow the day it all started but my flight was cancelled. Or maybe I chickened out. History doesn't relate...

8 October

Letter from Lenin to the Bolshevik Comrades attending the Regional Congress of

the Soviets of the Northern Region

Comrades, Our revolution is passing through a highly critical period …

A gigantic task is being imposed upon the responsible leaders of our Party,

failure to perform which will involve the danger of a total collapse of the

internationalist proletarian movement. The situation is such that verily,

procrastination is like unto death … In the vicinity of Petrograd and in

Petrograd itself — that is where the insurrection can, and must, be decided on

and effected … The fleet, Kronstadt, Viborg, Reval, can and must advance

on Petrograd; they must smash the Kornilov regiments, rouse both the capitals,

start a mass agitation for a government which will immediately give the land to

the peasants and immediately make proposals for peace, and must overthrow

Kerensky’s government and establish such a government. Verily, procrastination

is like unto death.

(V.I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin, The Russian Revolution: Writings and Speeches

from the February Revolution to the October Revolution, 1917, London 1938)

9 October

Report in The Times

The Maximalist [Bolshevik], M. Trotsky, President of the Petrograd Soviet,

made a violent attack on the Government, describing it as irresponsible and

assailing its bourgeois elements, ‘who,’ he continued, ‘by their attitude are

causing insurrection among the peasants, increasing disorganisation and trying

to render the Constituent Assembly abortive.’ ‘The Maximalists,’ he declared,

‘cannot work with the Government or with the Preliminary Parliament, which I am

leaving in order to say to the workmen, soldiers, and peasants that Petrograd,

the Revolution, and the people are in danger.’ The Maximalists then left the

Chamber, shouting, ‘Long live a democratic and honourable peace! Long live the

Constituent Assembly!’

(‘Opening of Preliminary Parliament’, The Times)

10 October

As Sukhanov left his home for the Soviet on the morning of the 10th, his

wife Galina Flakserman eyed nasty skies and made him promise not to try to

return that night, but to stay at his office … Unlike her diarist husband,

who was previously an independent and had recently joined the Menshevik left,

Galina Flakserman was a long-time Bolshevik activist, on the staff of Izvestia.

Unbeknownst to him, she had quietly informed her comrades that comings and

goings at her roomy, many-entranced apartment would be unlikely to draw

attention. Thus, with her husband out of the way, the Bolshevik CC came

visiting. At least twelve of the twenty-one-committee were there … There

entered a clean-shaven, bespectacled, grey-haired man, ‘every bit like a

Lutheran minister’, Alexandra Kollontai remembered. The CC stared at the

newcomer. Absent-mindedly, he doffed his wig like a hat, to reveal a familiar

bald pate. Lenin had arrived.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai

Sukhanov

Oh, the novel jokes of the merry muse of History! This supreme and decisive

session took place in my own home … without my knowledge … For such a

cardinal session not only did people come from Moscow, but the Lord of Hosts

himself, with his henchman, crept out of the underground. Lenin appeared in a

wig, but without his beard. Zinoviev appeared with a beard, but without his

shock of hair. The meeting went on for about ten hours, until about 3 o’clock

in the morning … However, I don’t actually know much about the exact

course of this meeting, or even about its outcome. It’s clear that the question

of an uprising was put … It was decided to begin the uprising as quickly

as possible, depending on circumstances but not on the Congress.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

11 October

British Consul Arthur Woodhouse in a letter home

Things are coming to a pretty pass here. I confess I should like to be out

of it, but this is not the time to show the white feather. I could not ask for

leave now, no matter how imminent the danger. There are over 1,000 Britishers

here still, and I and my staff may be of use and assistance to them in an

emergency.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2017)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval

cadet at Kronstadt

The proximity of a proletarian rising in Russia, as prologue to the world

socialist revolution, became the subject of all our discussions in

prison … Even behind bars, in a stuffy, stagnant cell, we felt instinctively

that the superficial calm that outwardly seemed to prevail presaged an

approaching storm … At last, on October 11, my turn [for release]

came … Stepping out of the prison on to the Vyborg-Side embankment and

breathing in deeply the cool evening breeze that blew from the river, I felt

that joyous sense of freedom which is known only to those who have learnt to

value it while behind bards. I took a tram at the Finland Station and quickly

reached Smolny … In the mood of the delegates to the Congress of Soviets

of the Northern Region which was taking place at that time .. an unusual

elation, an extreme animation was noticeable … They told me straightaway

that the CC had decided on armed insurrection. But there was a group of

comrades, headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who did not agree with this decision

and regarded a rising a premature and doomed to defeat.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first

published 1925)

12 October

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

On [Kerensky] expressing the fear that there was a strong anti-Russian

feeling both in England and France, I said that though the British public was

ready to make allowances for her difficulties, it was but natural that they

should, after the fall of Riga, have abandoned all hope of her continuing to

take an active part in the war … Bolshevism was at the root of all the

evils from which Russia was suffering, and if he would but eradicate it he

would go down to history, not only as the leading figure of the revolution, but

as the saviour of his country. Kerensky admitted the truth of what I had said,

but contended that he could not do this unless the Bolsheviks themselves

provoked the intervention of the Government by an armed uprising.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

13 October

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky is becoming more and more unpopular, in spite of certain grotesque

demonstrations such as this one: the inhabitants of a district in Central

Russia have asked him to take over the supreme religious power, and want to

make him into a kind of Pope as well as a dictator, whereas even the Tsar was

really neither one nor the other. Nobody takes him seriously, except in the

Embassy. A rather amusing sonnet about him has appeared, dedicated to the beds

in the Winter Palace, and complaining that they are reserved for hysteria

cases … for Alexander Feodorovich (Kerensky’s first names) and then

Alexandra Feodorovna (the Empress).

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917–1918, London 1969)

14 October 2017

The BBC2 semi-dramatisation of how the Bolsheviks took power, shown this week,

was a curious thing. Talking heads in the form of Figes, Mieville, Rappaport,

Sebag-Montefiore, Tariq Ali, Martin Amis and others were interspersed with

moody reconstructions of late-night meetings, and dramatic moments such as

Lenin’s unbearded return to the Bolshevik CC (cf Sukhanov above). The programme

felt rather staged and unconvincing, with a lot of agonised expressions and

fist-clenching by Lenin, but the reviewers liked it. Odd, though, that

Eisenstein’s storming of the Winter Palace is rolled out every time, with a

brief disclaimer that it’s a work of fiction and yet somehow presented as

historical footage. There’s a sense of directorial sleight of hand, as if the

rather prosaic taking of the palace desperately needs a re-write. In some

supra-historical way, Eisenstein’s version has become the accepted version.

John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World

, currently being

serialised on Radio 4, is also presented with tremendous vigour, and properly

so as the book is nothing if not dramatic. Historical truth, though, is often

as elusive in a book that was originally published — in 1919 — with an

introduction by Lenin. ‘Reed was not’, writes one reviewer, ‘an ideal observer.

He knew little Russian, his grasp of events was sometimes shaky, and his facts

were often suspect.’ Still, that puts him in good company, and Reed is

undoubtedly a good read.