16-22 July 1917

We would like to know, why did [Kerensky] consider it

necessary to move into the Winter Palace? Why was it necessary to eat and sleep

like a tsar: to tread on

elegance and luxury when the only real right to do this was the people’s; for in the

future it was to be theirs, as the Museum of Alexander III, as the Hermitage

and Tretyakov Gallery. Had Kerensky not been in the palace, the people’s rage

wouldn’t have touched a single trinket. Did the prime minister really not know

that the political struggle could, at any moment, fling him if not from

Nicholas II’s couch, then at least from his chair, that he was putting artistic

treasures in the most perilous danger by daring to live amongst them.

(L.M. Reisner in A.F.

Kerensky: Pro et Contra

, St Petersburg 2016)

16 July

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

I believe the Emperor and his family have been sent to

Siberia. I heard this last night. I wonder what effect it will have on the

people. I think Kerenski will make himself dictator.

( The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

17 July

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

Now the question that naturally and inevitably arose was

that of a dictatorship. Indeed, three days after Kerensky’s ‘appointment’ as

Premier, the Star Chamber appeared before the Central Executive Committee with

a demand for a dictatorship.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record

, Oxford 1955)

18 July

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

I met Kerensky again today, in his khaki uniform (he still

does not dare dress like a Cossack), installed like the Emperor in the Imperial

Rolls-Royce, with an aide-de-camp covered in shoulder-knots on his left, and a

soldier sitting next to the chauffeur … the great man of the Russian revolution

is in reality nothing but an inspired fanatic, a case, and a madman: he acts

through intuition and personal ambition, without reasoning and without weighing

up his actions, in spite of his undoubted intelligence, his forcefulness and,

above all, the eloquence with which he knows how to lead the mob – all of which

shows how dangerous he is … Fortunately, the career of a personality such as

this can only be precarious. Nevertheless, for the moment he is the only man on

whom we can base our hope of seeing Russia continue to fight the war, so

therefore we must make use of him ... but I fear that he has some terrible

disappointments in store for us, in spite of his blustering and in spite of the

Draconian measures he has proclaimed. And yet, in Russia you never can tell …

perhaps the people will lie down like good dogs as soon as they see the stick.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

19 July

Diary of Nicholas II

It’s three years since Germany declared war on us; it’s as

if we had lived a whole lifetime in those three years! Lord, help and save

Russia!

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

, London 1996)

Statement by the Provisional Government to the Allied Powers

In the inflexible decision to continue the war until the

complete victory of ideals proclaimed by the Russian Revolution, Russia will

not retreat before any difficulties … We know that upon the result of this

struggle depends our freedom and the freedom of humanity.

( Russian-American Relations:

March 1917-March 1920

, New York 1920)

Around the country, peasant revolts grew in violence and

anarchy continued, especially over the hated war, the catastrophic offensive

costing hundreds of thousands of lives. On 19 July, in Atarsk, a district

capital in Saratov, a group of angry ensigns waiting for a train to the front

smashed the station lanterns and went hunting their superiors, guns at the

ready, until a popular ensign took charge, and ordered the officers’ arrest.

Rioting soldiers detained, threatened and even killed their officers … By the

19th … the new commander-in-chief [Kornilov] bluntly demanded total

independence of operational procedures, with reference only ‘to conscience and

to the people as a whole’ … Kerensky began to fear that he had created a

monster. He had.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution

, London 2017)

20 July

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

The shadow of a military dictator grows larger and larger –

and I am not disinclined to believe that it is the solution of the question.

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright

, London 2002)

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Kislovodsk. The Grand Duchess [Vladimir] received me in her

cabinet de travail, and we counted the money which I had brought her in my

boots from Petrograd! It was in revolutionary thousand-rouble notes, which she

had never seen before.

( The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

21 July

Resolution from soldiers of the 2nd Caucasus Engineering

Regiment

[Our regiment] has allowed its ranks to commit a series of

tortures and murders of our citizens over nothing but freedom of speech. Within

its ranks there are ignorant men who have trampled upon all the Great human and

civil rights; they have dragged speakers off tribunes and even beaten up those

who suffered under the old regime for trying to attain freedom … We propose

immediately discovering the direct participants in all the crimes … and

arresting them and handing them over for trial without mercy or leniency. We

will not and cannot allow ignorant people who beat freedom fighters to death in

free Russia to go unpunished.

(Mark D. Steinberg, Voices of

Revolution, 1917

, New Haven and London 2001)

22 July

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

We awoke to an extraordinary situation of no government this

morning! The ministry all resigned last night – being in session until 5.00 AM

this morning.

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright

, London 2002)

Arthur Ransome in a letter to his family in England

You do not see the bones sticking through the skin of the

horses in the street. You do not have your porter’s wife beg for a share in

your bread allowance because she cannot get enough to feed her children. You do

not go to a tearoom to have tea without cakes, without bread, without butter,

without milk, without sugar, because there are none of these things. You do not

pay seven shillings and ninepence a pound for very second-rate meat. You do not

pay forty-eight shillings for a pound of tobacco. If ever I do get home, my

sole interest will be gluttony.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution

, London 2017)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

22 July 2017

Lenin called Kerensky a ‘Bonapartist’, other contemporary

commentators referred to him as a ‘little Napoleon’. The references to

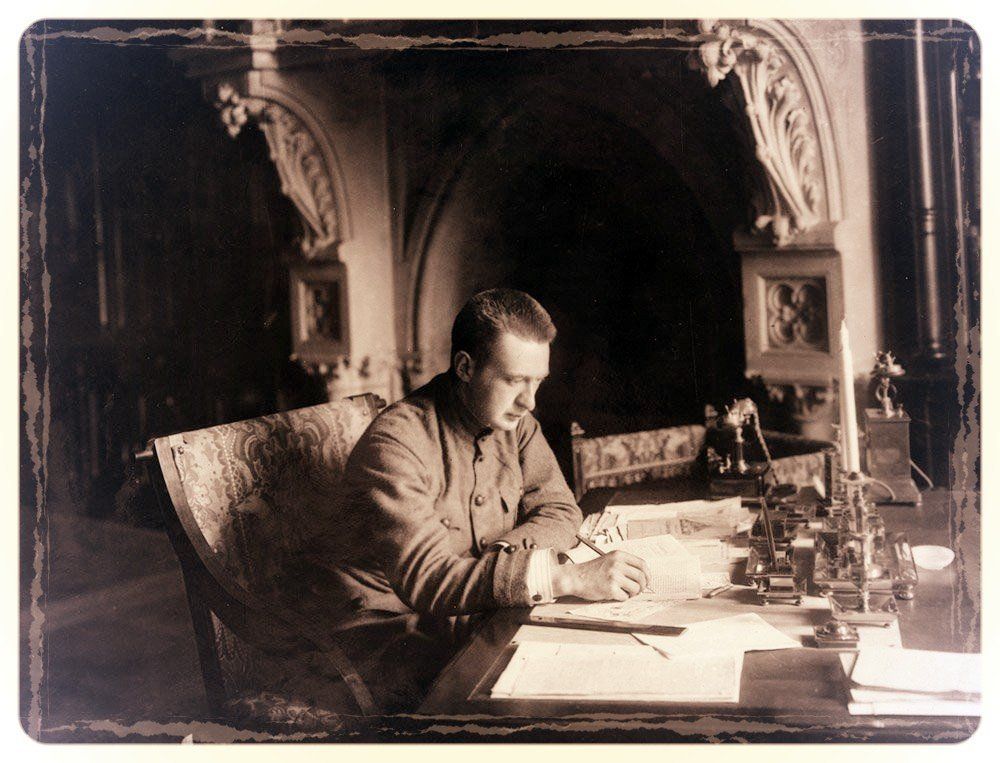

dictatorship in this week’s extracts are compelling. In retrospect, Kerensky's decision to move into the Winter Palace

in July 1917 on becoming prime minister seems a bit strange. He occupied

the former rooms of Alexander III, and was soon nicknamed ‘Alexander IV’.

Rumours that he slept in the imperial bed were not true; in fact Kerensky

removed the grandest pieces of furniture and portraits, and went around in his

trademark semi-military jacket. In his Interpreting

the Russian Revolution

, Orlando Figes describes the care Kerensky took over

his personal appearance as ‘all part of his vanity – and of his awareness of

the importance of public image to the revolutionary minister’. He even wore his

right arm in a sling during his tours of the Front, the result, people joked,

of too much hand-shaking. He was often photographed in this ‘Napoleonic pose’.

Perhaps the imperial instinct was not entirely foreign to Kerensky. The wife of

the ex-minister of Justice (whom Kerensky replaced) recalled him expressing a

change of attitude after visiting the tsar in Tsarskoe Selo, even admitting

regret that people had not really appreciated Nicholas II’s qualities. (There

were later rumours of Kerensky helping to fund an unsuccessful attempt to free the

imperial family a few weeks later, when they were already in Tobolsk – but

these remain unsubstantiated.) A ‘little Napoleon’, assuming the trappings of

office, making speeches in royal palaces – perhaps M. Macron, the new president

of France, should take heed…