5-11 March 1917

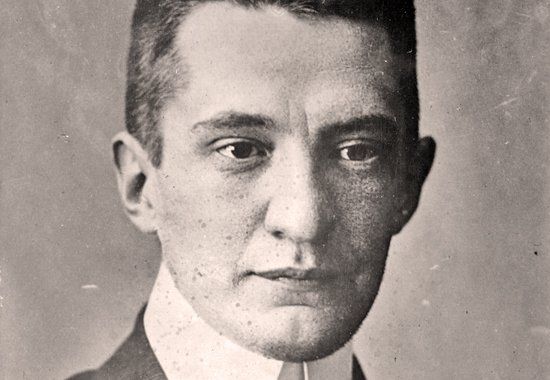

Alexander Kerensky, leading member of the Provisional Government

It was Alexander Kerensky who most represented the fraternal

and national ideal of the revolution. A member both of the Executive Committee

of the Petrograd Soviet and of the Provisional Government … Kerensky was idolized

by many as a symbol of the revolution – and with good reason. In the February

days, no other member of the Duma so boldly went out into the streets of the

city to voice support for the demonstrating workers and soldiers. None was so

ready as he to defy the tsar’s order disbanding the Duma. And Kerensky was the

most convinced and energetic advocate of the political coalition that united

the ‘bourgeois’ liberals and the plebeian soviets … that characterized Russian

politics between February and October. He literally ‘personified’ national

unity, and he was lionized in just this way: as ‘the genius of Russian

freedom’.

(Mark D. Steinberg, Voices of Revolution, 1917

, New

Haven and London 2001)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

It was a heavy load that history laid upon feeble shoulders.

I used to say that Kerensky had golden hands, meaning his supernatural energy,

amazing capacity for work, and inexhaustible temperament. But he lacked the

head for statesmanship and had no real political schooling. Without those

elementary and indispensable attributes, the irreplaceable Kerensky of expiring

Tsarism, the ubiquitous Kerensky of the February-March days could not but

stumble headlong and flounder into his July-September situation, and then

plunge into his October nothingness, taking with him, alas! an enormous part of

what we had achieved in the February-March revolution. But it was clear to me

that it was precisely Kerensky with his ‘golden hands’, with his views and

inclinations, and with his situation as a deputy and his exceptional popularity

who, by the will of fate, had been summoned to be the central figure of the

revolution, or at least of its beginnings.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record

, Oxford 1955)

It soon became obvious that Alexander Feodorovich Kerensky,

Minister of Justice, was man of the moment. His name seemed to be in everyone’s

mouth; in fact, it was rumoured that Kerensky himself was instrumental in

bringing about the abdication. So much is rumoured in these exciting days that

it is difficult to distinguish truth from fiction. I saw a picture of Kerensky

this morning and was surprised to see how young he looked; clean-shaven, with

an oval face, his appearance was in striking contrast with those heavily

bewhiskered and bearded generals and politicians … All eyes were now riveted on

the Provisional Government. Would the power wielded by that handful of brave

men spread its kindly influence throughout that vast country, bringing new hope

to the despondent, allaying the fears of the pessimistic, and assuring one and

all of the advent of a new era of hope, peace and prosperity?

(Florence Farmborough, Nurse at the Russian Front: A Diary

1914-18

, London 1974)

5 March

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French

Ambassador to Russia

I went out to see some of the churches: I was curious to

know how the faithful would behave at the Sunday mass now that the name of the

Emperor has been deleted from public prayers … The same scene met me

everywhere; a grave and silent congregation exchanging amazed and melancholy

glances. Some of the

moujiks looked

bewildered and horrified and several had tears in their eyes. Yet even among

those who seemed the most moved I could not find one who did not sport a red

cockade or armband. They had all been working for the Revolution; all of them

were with it, body and soul. But that did not prevent them from shedding tears

for their little Father, the Tsar,

Tsary batiushka !

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs

1914-1917

, London 1973)

6 March

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French

Embassy

People say that the Emperor is asking to be taken to

Tsarskoye selo, to be near the Grand Duchesses, who are ill. From there he

would go to England by way of Murmansk.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in

Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

7 March

Report in The Times

A cavalry captain today tried to gain access to M. Kerensky,

the Minister of Justice, on the pretext that he had a letter to deliver. As the

man’s attitude was suspicious he was searched, and in one of his pockets was a

loaded revolver. On being placed under arrest the officer snatched the revolver

from one of the officials and shot himself dead.

The Times

, ‘The New Regime in Russia’

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French

Ambassador to Russia

This afternoon I went for a walk round the centre of the

city and Vassili-Ostrov. Order has been almost restored. There are fewer

drunken soldiers, yelling mobs and armoured cars laden with evil-looking

maniacs. But I found ‘meetings’ in progress everywhere, held in the open air,

or perhaps I should say open gale. The groups were small: twenty or thirty people

at the outside, and comprising soldiers, peasants, working-men and students.

One of the company mounts a stone, or a bench, or a heap of snow, and talks his

head off, gesticulating wildly. The audience gazes fixedly at the orator and

listens in a kind of rapt absorption. As soon as he stops another takes his

place and immediately gets the same fervent, silent and concentrated attention.

What an artless and affecting sight it is when one remembers that the Russian

nation has been waiting centuries for the right of speech!

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs

1914-1917

, London 1973)

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman (Letter to Sir Arthur George)

Oh! Archie we

have had a week! As you may imagine, I have been in the streets all through the

revolution – constantly on my stomach in the snow with the police machine-guns

firing over me. You would have laughed to see me lying in the snow in the

middle of a street with a fat woman across my body and the machine-guns raking

the street. I am very, very tired. I saw a great deal and also heard a great

deal of first-hand news, all of which I

have written down from hour to hour … The first firing by the police was

in our street at 5.15p.m. on Saturday [25 February]. – Until Wednesday [1st], a

complete upheaval. By Thursday the police had been beaten and the Emperor had

abdicated. The new Executive Government only wanted a Constitutional regime,

but things have gone so far it will probably have to be a Republic; still,

Russia is a box of surprises … The fear is that the present Liberal-Radical

Government may become Radical-Red.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

,

New York 1919)

8 March

Memoir of Pierre Gilliard, tutor to the Tsar’s children

At half past ten on the morning of the 8th Her Majesty

summoned me and told me that General Kornilov had been sent by the Provisional

Government to inform her that the Tsar and herself were under arrest and that

those who did not wish to be kept in close confinement must leave the palace

before four o’clock. I replied that I had decided to stay with them. ‘The Tsar

is coming back tomorrow. Alexei must be told everything. Will you do it? I am

going to tell the girls myself.’ It was easy to see how she suffered when she

thought of the grief of the Grand Duchesses on hearing that their father had

abdicated. They were ill, and the news might make them worse. I went to Alexei

and told him that the Tsar would be returning from Mogilev next morning and

would never go back there again. ‘Why?’ ‘Your father does not want to be

Commander-in-Chief any more.’ He was greatly moved by this, as he was very fond

of going to GHQ. After a moment or two I added: ‘You know that your father does

not want to be Tsar any more?’ He looked at me in astonishment, trying to read

in my face what had happened. ‘What! Why?’ ‘He is very tired and has had a lot

of trouble lately.’ ‘Oh yes! Mother told me they stopped his train when he

wanted to come here. But won’t papa be Tsar again afterwards?’ I then told him

that the Tsar had abdicated in favour of the Grand Duke Mikhail, who had also

renounced the throne. ‘But who’s going to be Tsar, then?’ ‘I don’t know.

Perhaps nobody now.’ Not a word about himself. Not a single allusion to his

rights as the Heir. He was very red and agitated. There was a silence, and then

he said: ‘But if there isn’t a Tsar, who’s going to govern Russia?’ At four

o’clock the doors of the palace were closed. We were prisoners!

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

,

London 1996)

9 March

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to the Imperial

Court

The Emperor – who after his abdication had returned to his

former headquarters at Mohileff – was now styled ‘Colonel’ Romanoff, according

to his official rank in the army. On March [9] he was brought to Tsarskoe,

where he and the Empress were placed under arrest. When the news of his

abdication had first reached the palace the Empress had refused to credit it...

But, when the first shock was over, she behaved with wonderful dignity and

courage. ‘I am now only a nursing sister,’ she said. … Though, during their

stay at Tsarskoe, Their Majesties were under constant guard, and could not even

walk in their private garden without being stared at by a little crowd of

curious spectators who watched them through the park railings, they were spared

any ill-treatment. Special measures for their protection were taken by

Kerensky, as at one moment the extremists, who clamoured for their punishment,

had threatened to seize them and to imprison them in the fortress.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia

,

London 1923)

Report in the Manchester Guardian

M. Kerensky, one of the Russian Socialist leaders and the

new Minister of Justice, in an interview with the ‘Daily Chronicle’s’ Petrograd

correspondent, said: - ‘I must tell you frankly that we Russian Democrats have

been latterly rather worried about England, because of the close relations

between your Government and the corrupt Government we had. But now, thank God,

that is over, and our deep, strong feeling for England as the champion of

liberty will come into its own again.’

The Manchester Guardian, ‘Russian Democrats and Britain’, 22 [9] March 1917

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to the Imperial

Court

The United States Ambassador was the first to recognize the

Provisional Government officially on March [9], an achievement of which he was

always very proud. I had, unfortunately, been laid up for a few days with a bad

chill, and it was only on the afternoon of the [11th] that I was allowed to get

up and go with my French and Italian colleagues to the Ministry, where Prince

Lvoff and all the members of his Government were waiting to receive us.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia

,

London 1923)

Memoir of Princess Paley

The Embassy of England, on the orders of Lloyd George, had

become a centre of propaganda. The Liberals, Prince Lvoff, Miliukoff,

Rodzianko, Maklakoff, Guchkoff etc, were constantly there. It was at the

English Embassy that it was decided to abandon legal avenues and follow the

path of Revolution. It should be added that in all of this Sir George Buchanan,

the English Ambassador to Petrograd, was satisfying a personal grudge. The Emperor didn’t like him and he was

increasingly cool towards him.

Princess

Paley, ‘Souvenirs de Russie’, Revue de Paris 1922

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to the Imperial

Court

That

Princess Paley is gifted with a vivid imagination is no secret to me, and I can

but congratulate her on this chef-d’oeuvre … Needless to say, I never engaged

in any revolutionary propaganda, and Mr Lloyd George had our national interests

far too much at heart ever to have authorized me to promote a revolution in

Russia in the middle of a world war … Princess Paley, unlike my other critics,

has rendered me one service for which I am grateful. I have often wondered what

was the motive that prompted me to start the Russian revolution, and she is

good enough to tell me. The Emperor did not like me – he has received me at my

last audience standing – he had never offered me a chair. What more natural

than that after such treatment I should … try to bring about a palace

revolution?

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia

,

London 1923)

10 March

Letter from Aleksei Peshkov [Maxim Gorky] to his son M.A. Peshkov from Petrograd

My dear friend, my son, You should bear in mind that the revolution has only just

begun; it will last for years, a counter-revolution is possible, and the

emergence of reactionary ideas and attitudes is inevitable … The events taking

place here threaten us with grave danger. We have accomplished the political revolution

and now we must consolidate our conquests … And we must remember that Wilhelm

Hohenzollern could still play the same role in the rebirth of reaction as was

once played by our own Alexander Romanov I. The Petersburg bourgeois is capable

of greeting Wilhelm with the same applause with which he once greeted

Alexander! … Russia is now a free country and the German invasion is

threatening that freedom. If Wilhelm were to win, the Romanovs would be

restored to power.

( Maksim Gorky: Selected Letters

,

Oxford 1997)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

11 March 2017

Alexander Kerensky (1881-1970), the son of a school superintendent from Simbirsk, graduated in law in 1904 and specialised in legal aid. In December 1905 he was arrested and imprisoned for four months for possession of illegal literature. For the next six years he devoted himself to the defence of political offenders all over Russia. In 1913 he came to public attention for highlighting the government's antisemitic policies in the trial of Menahem Beilis. For this Kerensky was sentenced to eight months' imprisonment and denied the right to run for public office (though he was already a member of the Duma). He was a highly informed opponent of the Tsarist regime, but surely he could never have anticipated his sudden elevation to the forefront of Russia's revolutionary events. In the words of one historian, 'Kerensky's emergence as a popular leader in the first days of the February Revolution was phenomenal. He was everywhere, in the halls of the Duma, on the streets, in the barracks, voicing with impassioned eloquence the hopes and aspirations of the people. When the decision was taken to form a new government, it was clear to all he would have to be in it.' Kerensky's role in the Provisional Government will form part of the narrative of the coming months; how he saw it all ten years later is clear from the title of his 1927 memoir: 'The Catastrophe'. In the book he makes an interesting, though perhaps rather self-justifying, assertion about the importance of the Revolution in the eventual defeat of Germany: 'The Revolution succeeded in abolishing the autocracy, but it could not remove the exhaustion of the country, for one of its main duties was to carry on the War. It had decided to put the utmost strain upon the country's resources. Herein lay the tragedy of the Revolution and of the Russian people. Some day the world will learn to understand in its proper light the via crucis Russia walked in 1916-17 and is, indeed, still walking. I am quite convinced that the Revolution alone kept the Russian army at the front until the autumn of 1917, that it alone made it possible for the United States to come into the War, that the Revolution alone made the defeat of Hohenzollern Germany possible.'